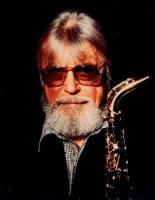

BUD SHANK

The timely emergence

The flute's voice

Sophistication, the Samba and the Search

Playing with big orchestras

Enjoying a more interesting life

Let's get rid of the categories

Food for thought

Improvisation: Can it be learned?

Bud Shank Today

Selected performances

With all the wandering around the world that I've done in the past thirty years or so, I never had the opportunity to come to Britain before. It's an adventure I've looked forward to for a long time. And I'm really doing it up; my wife and I took a sevenday drive through Southern England and Wales, before our twoweek stay in London for the engagement at Ronnie Scott's. I must say, the country is even lovelier than we expected; we talked to a lot of people who had done the same thing, and they told us we'd keep saying how pretty it is—well, we found it more than just pretty. The countryside over in Wales, all those beautiful farms and things—it really is gorgeous. You'll never find anything like this in the States. Naturally, there are things over there that you're not going to see here—the Grand Canyon or the Mohave Desert, whatever. But you can leave the Mohave Desert there, anyway! Ronnie's is quite a delightful club; our early shows have been very well attended, which has made us feel good. The second show, which started about 1.30 a. m., tended to get a little noisy sometimes; in our particular kind of group, that can be disturbing. But these are the things that happen in nightclubs. Other than that, everything has been great. Ronnie and Pete take very good care of the people who work there; all the facilities on and off the stand could not be better. It compares very well with clubs in the States; it's better than a lot of them. And we've had a very nice reception from the people at all times.

This is a different kind of jazz group—it's intended to be. The L. A. Four was put together as a concert group—with nothing particular in mind, but to see what would happen. We're involved with Laurindo, a classic guitarist, plus two, shall we say, older jazz players, and one younger jazz player. You put it all together, and this is what comes out. We're not striving for anything special, except to make this kind of a group work. We're trying to present our kind of music in a way that's a little bit different. Even including the old jazz standards that we play: rather than just start off with the melody, blow a while, fours with the drums and out, we're trying to do different things in the middle. Some of which will incorporate Laurindo's talents, some of which will just be aiming to be a little fresher and more varied.

Naturally; we're involved with Latin/ Brazilian things, because that's one of Laurindo's strong points. We're also involved with classical material; we do a lot of Bach things, and we're done some Ravel things, incorporating our individual assets with what Laurindo does in the most effective way we can. That's also a nice challenge, and we're enjoying it.

You have our recording of the Adagio movement from the Rodriga guitar concerto? What we did on that was to take all the instrumental parts that the orchestra plays, and make another whole line—which is essentially what I play. Sa I'm the whole orchestra—but it makes almost another whole solo line out of it. An interesting line to play, anyway. When you're taking a piece of music written for a full symphony orchestra and having just four guys play it, it opens some doors and creates some challenge you can respond to.

When we first put the group together five years ago, it was essentially an extension of those jazz/ Latin albums Laurindo and I made in the 'fifties—because that's all the music we had. But as we started exploring more and more, it evolved to the things we're into today, and we've completely eliminated all that old stuff. Though we didn't plan it, it was something to latch on to, to start with. We're not through exploring what we can do with this group, by any means. We will rehearse, and everybody comes up with an idea: "I'd like to do suchandsuch a song in this way." Then we’ll play around with it, put it on a cassette; somebody will come up with another idea, we'll tape that. Laurindo takes all this home, brings it back later with his part worked out and a framework for us—and away we go on another one. Again, some of 'em are standards, some are originals—a fragment of an idea of one of us. We'll then rehash them again during more rehearsals, and that's how they take shape.

Yes, it's a cooperative group. Originally, Shelly Manne was with us; then, when he left, and Jeff came with the group, Jeff was put on a retainer payroll—but now he's a full member of the group also. We each have different jobs to do. Ray Brown takes care of the booking of the group, through his agency; he's got a small booking agency, that involves mostly Milt Jackson and our group. And Laurindo, as I said, primarily takes care of writing down the music; he's also the librarian. I take care of all the business and finance—and the money. Jeff has several jobs: he calls all the sets, would you believe—he picks all the music that we play every night—and he picks the uniforms that we're going to wear. We've worked it out so that everybody has a different main job; also, if anybody has any comments about somebody else's job, they're valid and are listened to. No one person's word is final, about anything.

It would be very difficult for there to be one leader in this group. And it takes a load off one person having to do everything. I've been on the road with groups of my own in past years, and the logistics of keeping a group on the road and together, taking care of this, taking care of that, by the time you get to the job at night you're wasted. I would rather have less things to do, let other people do 'em, share the responsibility and, if necessary, share the glory. It really is difficult for one guy to take over everything. Economically, it's not really feasible to carry a fulltime manager along with you on the road; so that puts it back on the leader's shoulders. It's much better this way. However, in the States we do carry a road manager with us, who takes care of all our equipment and everything. But he's not on this trip—again, because of money; we couldn't afford it. In America, he's with us almost all the time—and that's another worry off everybody's shoulders.

We try to put together three–month segments of work. We're involved in one of those now, and after this is over we'll probably take two, maybe three months off; then we'll set up another three months. If we totalled it up, we work around six months of the year with the group. The other six months of the year, we're all out doing our other things, whatever we wish to do. Laurindo does concerts, by himself or with his wife. Ray does some things with his own group, and he does a lot of studio work. I do lot of studio work in Los Angeles, and work with my own group by myself. Jeff does many different things, including working with Herb Ellis's group. We're free to do whatever we like, as long as no two of us work the same job at the same time; like, Ray and I would not work together in a club or concert away from the group. So this way, the travelling is kept down to just the right amount.

Our main intent with the group is to do concerts; we try to do as many as we can, as opposed to clubs. At the same time, we've proved to ourselves—or rather, reproved—that the best place for new material to be born, and to develop, is in a club. So, from a musical standpoint, it as necessary for us to do clubs; we've tried to balance it out, do some of each.

Most definitely, a club is where I play the best.

Up until maybe 1963, I was always working with a group of my own, on the road or in Los Angeles. Towards the middle 'sixties it seemed that jobs for all jazz musicians were getting harder and harder to get, and jazz record dates were harder to came by. They had me doing commercial records; I had a couple off you'll excuse the expression—hit records, that I was really not that proud of, but that's what the record company had me doing. And things sort of just dwindled away. The studio thing became more appealing—initially, actually, because I needed a place to work—and I went more and more into it. About that time also, or a little earlier, studio work opened up as regards what jazz musicians like myself could do. There was a market for our talents in film and television work. In the early 'fifties, when I first became a professional musician and first went to Los Angeles, jazz musicians, across the board, were not permitted to be on a film score. In their minds, jazz players couldn't even read. But this all changed in the middle 'fifties, and by the end of the ‘sixties I had a very good thing going in the studio. I had the nucleus of a quartet that I worked with; maybe every three months I would work a few weekends at Donte's, and that was about the extent of it—and a couple of concerts, whatever.

I guess it was in the period 1973'74 that the whole jazz thing started to turn around; there was a new interest in what jazz musicians were doing—especially the guys who had been around in the 'fifties. Ray Brown and I were both immersed in studio work, and I think we saw this coming. And that's essentially why we started looking around for something to put together, and hit on this L. A. Four thing. We saw that there was going to be a market for something, if presented right—and we were right.

Jazz musicians are making records and working clubs now; guys who, like myself, had been buried during the 'sixties, are coming back out again. A whole bunch of born–again beboppers! My birthplace was Dayton, Ohio, on May 27, 1926. I started on clarinet at the age of ten; how that came about has always been a mystery to my family and to me, I was born and raised on a farm, about as far removed from any kind of music as you can get, other than the radio. I just had some kind of a desire to play something or other; there was a piano in our house, which I used to bang on, but it really didn't interest me. From hearing the bands that would be on the radio in the mid 'thirties, for some reason I was fascinated by the clarinet. Which changed quickly, because by the time I was twelve or thirteen I had my first saxophone—which was an alto. And I was one of the few people around that area that played saxophone or anything like that. I changed to tenor very shortly after that, and until I was with Charlie Barnet.

From the time I was fourteen until I entered college, we moved around a lot, as my father was in the Army at that time. I lived in Mississippi, Georgia, and ended up in North Carolina, which is where I graduated from high school. As for influences—it must have been the Benny Goodman/ Artie Shaw thing that got me interested at first; as I progressed, and got into the saxophone I was more into Lester Young than anybody. Then Charlie Parker came on the scene, and some of his records would come filtering down to Durham, North Carolina.

One of the big things that was a great help to me, at fifteen or sixteen, was the fact that a lot of black bands came through North Carolina on the road at that time, playing dances for black people only. Some great bands—one of the best I ever remember was Billy Eckstine's band, that had people like Dizzy Gillespie and Dexter Gordon on it. He came through there several times, and there were a few white guys who were permitted to be way up in the top balcony, looking down on the thing. I learned more, I think, from those circumstances than anything else. There were many other bands other than B's band—Ellington, Basie and a lot of lesser–known black bands—but that's the one that always stuck in my mind.

Copyright © 1979, Les Tomkins. All Rights Reserved.