TERRY GIBBS

To speak of technique

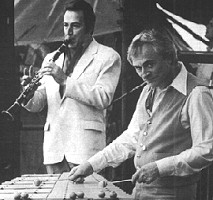

Buddy De Franco and Terry Gibbs

A vibes virtuoso

Jazz - Rock and me

To speak of technique

Success of the partnership with Buddy De Franco

My approach to the vibes

The return of straight-ahead jazz

To speak of technique—yes, I do know my instrument well. When I listen to those things I recorded with Chubby Jackson's group in Sweden in the 'forties—I was braver those days on records than I am today, I think. It's not that I'm more careful today; it's just that I had so much technique then that I didn't know about anything but playing double time all the way through. On "Boomsie" I played a two–bar break that I don't think I would attempt to do today—I didn't really care. By the way, you recorded right on wax then, and it was all one take—you couldn't do two takes; it was almost like recording live. I look at it as gambling now, but I didn't then. I played four million notes, and they all came out technically right.

I pride myself on having a good technique—but, I must tell you, I have to work at it. More now that I'm actually back to playing jazz again. Not that I gave up, but I have a very comfortable job there conducting for Steve Allen, and I got a little lazy for a while. Now, when I have shows to conduct and I don't play any music, I'll practise an hour or two every day to keep myself in shape, because I couldn't do the things I do in a club otherwise. In fact, what I always do before I go to work: I take my mallets and I practise on a chair, just to get my hands in a little bit of shape.

A challenge to me sometimes on a club set is to play something hard on the first tune. What I've been doing also: somewhere in the tune, after I play fours with the piano player, I'll have everybody stop and I'll play alone.

What that does for me is to put me in a spot—I either die alone or I win alone—and I must maintain that time. If I can do that, then I feel comfortable for the rest of the night. It's almost like practising, but it's not; it's opening up your mind, and getting command of the instrument. On that first tune, I'll get into what I want to get into—then I'll play twenty more after that. I'll gamble with everything in the world.

I have changed vibes sets. I have five sets at home; one which was my favourite for a lot of years is the first amplified set they made, with little microphones in each resonator—but it's got to the point where they've got shot now. Whatever I say on stage comes right through here.

So I have another set that I've been using with my big band, that I can hear well; it's a new amplified set that the Deagan company's made, and a very goo one—the best one they ever made. The Polytone amp that I found to be ideal for that instrument I had to buy myself, because they don't give you anything for nothing. I hit hard when I play, and with any other amp, if you just have it a little too high, you get a thud—with this, you don't get that.

On the question of four–mallet playing—Gary Burton is a phenomenon with the four mallets; boy, he really is something else. He does some things that are scary. But most of the guys who play with four mallets today are shucking, because with four mallets you can get away with things that you couldn't with two mallets. You take two away from them, and ask them to play a line and swing—they don't know what it means. With four mallets, you can play a wrong note and it'll sound dissonant, because it's part of a chord; any four notes can make any chord—even if it's wrong, it might be a strange kind of chord. I guess my big influences were horn players like Bird and Diz, and they never played more than one note at a time—they played a line, and that's how I like to play.

When I play with Buddy De Franco, I use four mallets for a background on ballads, or maybe to comp behind him. I like to do that, but as far as my solos are concerned, I like a line, and you really can't get it out with four mallets.

Songs like "I Got Rhythm" and "Stardust" have one note at a time; playing four notes at a time, it wouldn't get the feeling I like. But Gary Burton—of all the guys who play four mallets, he's the giant.

There are some guys, though, who can play four mallets and swing with two—like Victor Feldman. Incidentally, of all the vibe players, he's my favourite. But he's got locked into studio work to a great extent. In fact, I spoke to Victor two days before I first came to England, because I wanted to find out a few things about it. I was due to play at Ronnie's, and when he'd been in London a couple of weeks earlier he'd told Ronnie: "For Terry Gibbs, get a drummer who can swing and play fast." And Ronnie certainly did—he got Allan Ganley; so I was very fortunate. The whole rhythm section was just fine; and besides playing so good, as people they're nice. Which is very important, you know. For me, all my groups have been that way—if I cannot get along with a guy offstage, then I can't get along with him onstage, and there's no rapport there. It has to be fun.

Because of finances, most of us are forced to go out alone and play with whatever rhythm section they provide for us at a club. We were lucky here, but I just played with two rhythm sections in the States where it wasn't so.

In one case, the piano player was great, but the time. . . I didn't know when to come down with my mallets; I played double—time runs, and I wasn't sure if I should end up here or there. The other place I played, the drummer was fairly good, but the pianist just didn't know how to play in a rhythm section, and he never gave me the chord changes that I was looking for in anything.

I'd really love to bring my big band over here, and I'd want to bring the whole personnel, exactly as we have it. Because, to start with, my book is completely marked up. Some of the guys who've been there all these years have never marked something like "going from 60 to 80"—they just know it goes from 60 to 80. The late Joe Maini used to be my lead alto player, before I moved to New York; when I came back to California, I started the band again, and Bud Shank—a great saxophone player, who can read anything first time—played lead alto with us. And Joe Maini was the type of guy who, when he'd played an arrangement twice, if it was ten pages he never took it out again—he had it memorised. He never marked anything. So at the first few rehearsals we had with the band, every time we ended a tune, Bud played eighteen bars alone, because he just played the music like it was written. Finally, Bud learned the book, and knew where to go.

Then a guy like Conte Candoli—his parts all have on them a caricature he does of himself, featuring his nose, so you know those are his parts, If Conte was out of the band for a year, that book would belong to him when he came back.

There are certain guys—when they're there I feel very confident. One is Conte Candoli, because I love the way he plays. A great loss to us now is Frank Rosolino. ..what a terrible shame his death was—still none of us can understand that. But there are certain musicians—like Tiny Kahn, Joe Maini, Frank Rosolino—who will only be remembered for the joy they've added to the world.

In my band, all the guys loved Frank Rosolino's sense of humour; the way he just said off–the–wall things. Any time Frank was there, I would do a thing—I'd say: "Here it is. .." snapping my fingers apparently to kick off a chart; sometimes I'd go on for five minutes: "Here it is. . . here it is." And I wouldn't play a note; then I'd stop, and say: "Wait a minute", and I'd ask Frank any crazy question, like: "How's your feet? or "How's your shoes?" He'd come up with the dumbest answer—and the band would fall down on the floor laughing; you'd never seen a more unprofessional–looking band. From there on in, it was pandemonium—the band would really sound good.

I believe I lose control of my band after four bars, but it's something I do on purpose. Everybody has a personality, and I like it to come out—when they're not playing. When they're playing, they play the heck out of the music. If a guy's a funny guy, and I'm saying something on the mike, and he can add to it without getting in my way—beautiful. I want everybody to feel comfortable there. I run a loose band—I like that, but once we play the music I'm very serious about that, and so are all the guys in the band. You don't want any clowning with the music—it's too good to be played with.

The thing is, these guys are pros; if I'm leading in a certain direction, they'll let me finish what I'm doing—then they can say whatever they want to say. And I'm a good straight man; somebody will say: "Hey, Terry," and I know he wants to get into something—so I'll lead him; it usually breaks up the whole band, as well as the audience. And it loosens up the band to a point where it's fun.

Somebody hit it on the head one time; there's an engineer in California called Bill Puttnam—he says he knows why my band sounds so good. He says we never open up with the first set—we start out with our third show! Because I don't believe in warming up—I like to hit 'em on the head immediately. I think that works—if you hit the audience immediately rather than building up to it, then you can relax.

One thing I must mention: I have a book coming out, which is intended for out–and–out beginners on the vibes; actually, it's a beginners' book of learning ultra–basic harmony and theory. I wrote as if I was teaching a seven–year–old child. Before I wrote it, because I'm not going to write another instruction book ever, I spent a lot of time looking at four million other instruction books. I found that what they don't have is pictures of how to hold the mallets; so my book has sixteen pictures showing how to hold them—right and wrong. I think it will be very valuable to any piano player who wants to learn vibes, or any drummer who knows nothing about harmony or theory. They allowed me to use repetition: whatever—I wrote on a C scale, they let me do on every scale. It cost a lot more money to put it out, but that's the only way I would do it. There's a picture of a vibe set on every page; so it's really that simple. I'm very bad at putting toys together, and doing things like that; I can't learn from a book well.

So I wrote a book for people who can't learn easily from a book. You have to see it—that makes all the difference.

Copyright © 1982, Les Tomkins. All Rights Reserved.