TERRY GIBBS

My approach to the vibes

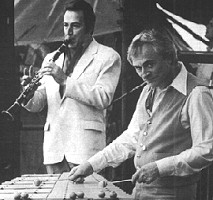

Buddy De Franco and Terry Gibbs

A vibes virtuoso

Jazz - Rock and me

To speak of technique

Success of the partnership with Buddy De Franco

My approach to the vibes

The return of straight-ahead jazz

Your son is now a drummer. You played drums yourself at one time, didn't you?

Yes—I still do once in a while. In act, I did in Stockholm recently. Zoot Sims is always starting a jam session. . . Zoot was on. the show, and Al Cohn, Bill Watrous and a whole bunch of people; we had a great rhythm section—Alan Dawson on drums, Red Mitchell on bass and Hank Jones on piano. Can't beat that—it was that good. Anyhow, Zoot started a jam session one night; Red Mitchell played, Jerome Richardson. There was only a photographer sitting there; he was playing a little drums—so I got up and played some drums. Until the real drummers came in—Ed Thigpen and Alan Dawson—I figured I'd better let them play. Yeah, when I was a kid, I had a scholarship to Juilliard as a timpanist—that was actually my best instrument I played legitimately.

In general usage, of course, the vibes are considered to be just part of the percussion family—just an accessory, as it were. It's only people like you who brought them to the forefront, to be recognised as an instrument in heir own right.

I feel good about that, when I look I back. You don't want to sound like an egomaniac when you say these things—but I'm probably part of that bunch of guys that helped bring the vibes to the attention of younger players.

I hope I am, anyhow. Well, in the bebop era, I think it was just Milt Jackson and myself, really, for a long time. Then Teddy Charles came around, and Don Elliott, Joe Roland, Eddie Costa came in. Now there's a whole bunch of young players who play well. I think most of the young vibists now are trying to play like Gary Burton.

Yes, I hear Gary's influence in the work of Don Friedman.

And Don Samuels too. Apart from Gary, who is in a class of his own, the outstanding four—mallet players are Mike Mainieri and Victor Feldman—who is my favourite.

In actual fact, what Gary's doing now. . . I don't think he's playing jazz any more. Like, what he and Chick Corea put on tape in those albums—it may be called jazz, but I think it's gone beyond that. It's almost classical—sounding. Yes, classical improvisation—I think that's what I have to call that. It's great.

I would like to see what they worked from, to do what they did; I'd like to know if they had some chords in front of them, or what—because it's very interesting, what they do. Now, Buddy (De Franco) and I—we take a tune, and use its chords, but for what they're doing, they must have some kind of structure somewhere. It's not just the tune they're working on. Gary can do a lot of interesting things—he bends notes, he glisses.

It's very appealing—that wow–y sound he gets with that little mallet. . .

Yeah—I think it's a mallet without the yarn on it. I've been doing it, but you can't gliss enough because it has yarn on it. I do it in some different ways. I've been deadening notes and playing that way, but it's like anything else—somebody picks up what you're doing, and goes from there.

Have you found that instruments have improved over the years?

You mean like a vibe instrument? No, they haven't. In fact, it's a drag, because I have an idea—which I can't tell you about; otherwise I wouldn't be able to do it—for a completely different set of vibes. I mean, it would have to have the same keyboard, but it would be a set where you could do so much more. They've gotten to a point right now where they're so expensive—it's really a shame.

They're probably even more here, but in the States to buy an instrument like I have is $4,800. Now, when a kid wants to study a trumpet or a violin, he can go rent one.

You can't rent a vibes set—it costs you a hundred dollars a day to rent one of those. So how's a young kid going to get into playing vibes? Unless he does it in school—then he has nothing to go home and really practise with. Because you must practise.

Initially it's a deceptive instrument, in that you can get something out on it right away. . .

Oh, you can pick out with one hand, sure. But the thing is, even if I don't play for a spell, I know it. Once in a while, when I work with Steve Allen, I'll conduct a show, and if it lasts a bunch of months I don't get a chance to play. I start out by practising at home, but then I get so busy with the writing, and conducting, and meetings that I stop after a certain amount of time. Then, when I have to go back to playing, to make a sound is hard—you over–hit the instrument sometimes. It's not just being stiff—especially if you're playing jazz—it's getting your mind working. Your mind has to get to your hands, so they go to the notes you hear. Then you may hear the notes, but not make the sound you want to hear—that throws you off completely.

So practise is essential. And they've got to go naturally, by themselves; you can't just say: "I'm going to do this"—it doesn't work that way.

Some pianists or drummers who acquire vibes may regard it as an easy double. Obviously, you'd advise them otherwise.

I would—I do. My book finally I came out—it's an absolute beginner's book for a vibe player. Actually, I was seven years old when I started to play, and I've written a book geared for a seven–year–old child—because I believe we're all children when we go to study something completely new. For drummers, if they know nothing about music at all, it's the simplest harmony and theory book you'll ever find. Repetition is the name of the game. . . whatever I wrote for the C scale went for every scale; it was just repeated, and the keyboard is shown for everything. Also, there are sixteen actual pictures of how I hold my mallets: right and wrong positions—that's another thing that most books don't give you. So a piano player, if he wants to learn vibes, can get the book and from these little exercises and hand movements he can be able to move around the instrument. A drummer will be able to follow the pictures, but he'll also learn basic harmony and theory.

This is specifically your way of holding the mallets, rather than anybody else's?

It's my way completely. They're all short mallets, like I play. I'm not saying it's the best way to play, but it's a proven thing with people that I've taught, to give you some technique that other vibe players don't have. I can't teach talent—that has to be something that you're born with—but people that I've taught can play faster than I can. Now, if they make use of it—that's something else.

You hold your mallets right at the beginning of the stick, don't you?

Yes, it's a finger system I have; this way I can get more flexibility—you're playing the instrument, not the mallet. It's held on your fingertips. You know how drummers get that kind of thing, with their fingers? Well, it's much harder on vibes. You hit the drum, it bounces up in the air; there's not any bounce on the vibes—so you have to use your fingers right.

How does your mallet approach compare with, say, Milt Jackson's?

I don't know. To start with, I don't think Milt Jackson's thing is a technical thing. I'm not talking about just to play jazz, but to play the instrument legitimately—to learn how to play xylophones, and make what they call a 'roll'. Milt's bag is to play good jazz—which he does. This is so you can take anybody and make them a good xylophone, marimba or vibist—that's what it's for, with the book. From there, you have to have a teacher—and you've got to go out and play. If you want to be a fighter, you' ve got to get in the ring, and get hit in the mouth, so you can protect yourself. Same thing—you have to go and jam, and have somebody tell you that you stink, and get out, and keep doing it till you get it right.

What are your thoughts about using or not using the motor?

Well, I like the sound of the vibrato. I mean, it's all according to how fast you want to use it. Milt uses it very slow; Red doesn't use it at all. I don't use it as slow at Milt, because I play more notes than Milt does, see; it gives you more brilliance when you have it a little faster.

Once again, it's the person who's playing it—the personal sound that you want to get out of the instrument. Lionel, I think, keeps it very fast—specially his old records, where they didn't have a motor control.

The way Red works it is having an amplifier.

I have an amplifier, but you know what I have it for? For me, it's a monitor—so I can hear myself. I can get a lot more technique on the instrument, because I don't have to lift my hands as high to bang. Hearing myself, I make a lot more runs now than I ever have; I can stay very close to the instrument—then, when I want to whack it, I can do that. It helps, too, when you get a bad P. A. system in a room. You remember those live albums, like "Explosion", that I made with my big band? I never heard one thing I did till I listened to the playbacks; we were playing for an audience in a club, and we were set up like that. When you have sixteen guys playing behind you, with the brass section hollering. . . I wasn't sure if it was good or bad; I thought I was going in the right places, and luckily I was. You could hear yourself—but not like you can with this instrument now.

In recording, the tendency is for musicians to wear headphones to hear one another. Do you do this?

Never. When I record, I try to stay way from anything that's not natural. In fact, one of the best ways to get a sound is to go in after the band, if you're playing with a big band, when they've put their tracks down, and put the earphones on. Then you can play four million takes until you get a chorus out you want—but it stinks. It doesn't have the natural feeling. When a band gets a little faster—say, it rushes a little bit—it's because you're all getting exciting at the same time. The other way, if the band is rushing you have to rush whether you feel it or not; you either stay up with it or lay behind. That's why when I record live we set up just like it is normally in a club—not having any guards and shields around the drums and all that. I don't want that feeling—I want the feeling of recording like I'm playing. Just the true thing; whatever comes out, comes out. But a lot of guys take the easy way out.

You feel that jazz must be spontaneous, whatever it takes to capture that on record?

Yes, I do. I did an album recently that'll just be in Japan; it was for a Japanese label. I had Lou Levy on piano, Al Viola on guitar, Andy Simpkins on bass and Jimmy Smith on drums. We went into the studio and, once again, they were going to have the vibes miles away—isolate me so they could get a good sound. I said: "No—I want to be where I can hear the drums; I need that feeling. So it's up to you—you find the best thing you can with how I want to be." And they did that. What they did: they put me through the amplifier on one track. . . see, with the amplified vibes I have, unless you have mikes in front it doesn't pick up the vibrato, because there's a little connection to each bar, but when it goes through the system you just get the sound of the bar . . . so, to mix it right, we had to have two mikes right in front of the vibes, picking up the vibrato. Then they put 'em both together—and did a great job. The recent live album with Buddy De Franco was done the same way. And that's even harder because the drums can leak right through the vibe mike.

They didn't want to do that, but I said: "If you don't want to do it, then don't record us." This way, when you can just play—I think that's the truest thing to have on a record. Our job is to make good music; the recording people's job is to pick us up.

Would you say recording techniques have improved a great deal since, say, those original quartet sessions of yours with Terry Pollard on piano?

Oh, yeah—but they made a good sound then. Of course, in the studio now you have everything in the world; you have twenty–four tracks—you can pick and take as you like. I don't know how these guys did it, but on the one for Japan, somewhere along the line there was a whack from something—they just took it right out; there was no problem. In the old days you couldn't do that; if somebody made a little sound, you stopped the take and did another one. The only one that they actually let me do that departed from this policy was that first album, with Terry Pollard, when I signed with Mercury Records' EmArcy label—the one where we recorded "Seven Come Eleven". You weren't doing live albums those days, because I don't think they were prepared to have all that equipment, and it probably cost too much money. But I wanted to do an album in a studio like I would do it in a club: I wanted to talk or shout "Yeah!" if I felt like it, or play another chorus if I was in the mood to. They agreed, and we brought in a few bottles of liquor and had a little party among ourselves. As a matter of fact, we were having so much fun playing and the drummer, Nils—Bertil Dahlander, was drinking quite a lot; after about the eleventh tune we heard a big thud—he'd fallen off the drum stool and passed out completely. He's six foot two—we couldn't lift him; we had to leave him in the studio till the next day. When we came back, he was still there on the floor, sleeping. Anyhow, we got what we were looking for—we got a lot of spirit on the album. And that album made a lot of noise for that little group I had then. I'd wanted to get away from the usual studio problems; first of all, they play back every take for you, and it's very hard, when you hear yourself playing something good, not to try to sneak it in on the next take. Then it becomes more contrived. You say: "That's a nice thing I played—I'm going to put it in next time." It reminds me of a story, of something I did to Red Rodney when I was on the Woody Herman band, on a tune that was called either "That's Right" or "Boomsie"—they changed the name. We were playing fours—Red, myself and I forget who else, on this blues thing. And Red kept playing the same series of phrases for his four bars, even though we kept making take after take. I was trying to play different things, and finally, on the take we took, I came in before Red on the first chorus—and because it had stayed in my mind, I played his four bars! So when he came in it, sounded like he was copying me! I stole Red's solo! It's funny how things can stick in your mind like that.

An album I did twelve years or so ago just came out. I was working in a little club with Walter Bishop, Jnr on piano, Louis Mackintosh on bass and John Dentz on drums; it was Friday, and they said we had to do it Monday. So I went home Friday night, I wrote six tunes, and I brought 'em in Saturday to show the guys. We played 'em; then I went home again, stayed up all night and wrote six more tunes. When I came back the second night, after we played one of the tunes, Louis Mackintosh said to me: "Terry—have you ever heard of a tune called `Watermelon Man'?" I said: "No." He said: "Well, you just wrote it!" Driving home the night before, I must have heard Herbie Hancock's record on the radio—it was new at the time—and when I sat down at home it had lodged in my mind, and I wrote it note–for–note! It's lucky that Louis told me—I would have gotten sued by Herbie!

Well, that's probably how you do get instances of people apparently plagiarising somebody else's song. They've heard it somewhere and it's stayed in their subconscious. In any case, with any kind of creativity, you can't have everything completely original at all times—it just has to be as it comes.

I think so—I don't think anybody just goes out to steal anything. You know, somebody just gave me a Charlie Parker broadcast—it was Jay Corré, the saxophone player, when we were working with Steve Allen in Atlantic City. He gave it to me because the disc jockey, Symphony Sid, mentioned my name on it. It was after Dizzy and Bird split up, for whatever reason—they put 'em back together for a week at Birdland, with Bud Powell, Tommy Potter and Roy Haynes, and they broadcast it this time. I listen to it—it's Diz and Bird at their very best—and I think to myself: everything I hear Charlie Parker playing, every saxophonist is playing today.

They're still trying, but nobody's come up to him yet. But every one of those things that were his are clichés that everybody's playing right now. Yes, they've become part of the language.

You've heard a lot of people play like Miles Davis, then Clifford Brown, then Freddie Hubbard—from that same school—whereas nobody could play like Dizzy.

That's because whatever Dizzy did on the trumpet was twenty times harder—specially those days. On this particular broadcast, Dizzy was phenomenal—he was playing in the upper register in a way that I haven't heard from anybody else since then.

Over the years, though, Dizzy seems to have mellowed down a lot.

Well, Dizzy's become more of a show person—but don't fool with him. I mean, get on a stage with him, and if you look to do him in, forget about it! By the way—there are three people that you never try to do in onstage—and I'm talking about cutting. One is Dizzy; another one is Lionel Hampton—you never fool with him at all, because he'll leap over the tom–toms, do a somersault and hit an A flat at the same time. The other one is Buddy Rich—if you fool with him, watch out, because he's the master of it. We worked with Buddy a few months ago, and he's better than ever—he really is.

Yes, I had to get his version of the "deserted in the desert" story. It was fascinating to hear how he turned the story around to his own advantage.

That's right. The way I said it was the truth; he's forgotten, but I wouldn't forget it, because I idolised Buddy Rich in those days. It's like: Benny Goodman won't remember something that happened between he and myself, where I would, since I idolised him. When you're young and you idolise somebody, you don't forget those things. But Buddy was pretty close.

It was probably a bit of both, actually.

Yes. That was a great part of my life; it's great to reminisce about it. Whatever it was, I'm glad it happened.

You were blazing trails, and there was more of a risk about it.

It wasn't a business—you were there to play. And I intend to go out of the business the same way some day; I intend to be that rich to where I can have a little place of my own, that holds about seventy or eighty people. I'm going to give it to my best friend to run for me; it'll be his place. I'll hire a resident trio, and leave my vibes there.

As I did when I started oft, I'm going to play when I feel like playing. If I want to go on Tuesday night, and if I play four bars and it sounds good, I'll stay there and play until nothing happens. If it stinks, I'll go home. Because when I got into the music business, it was for the reason that I loved it. Unfortunately today—or fortunately, in that you have to make a living—they tell you to play at nine o'clock, or eleven o'clock or one o'clock. Whether you're in the mood or not, that's instant composing—you have to get up there and do it. I'm never going to quit, but I'd like to be able to choose my playing times. Even if you had four million dollars, I think the challenge would still be there to go out and make a living—simply because that's the only way you'll know people want you, by calling you to come and work. That's the good feeling about Buddy De Franco and myself; people come in to see us and say: "Would you play my club?" and "Will you come and do the festival for me?" We know we're wanted.

Copyright © 1982, Les Tomkins. All Rights Reserved.