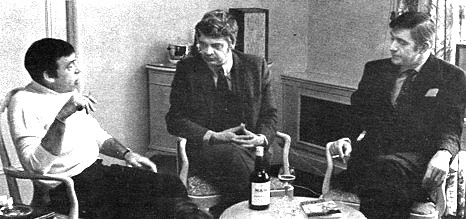

Three

famous instrumentalists, now bandleaders—who normally wouldn’t meet—gathered

together in a room at London’s Dorchester Hotel and talked on a wide range

of subjects. BUDDY RICH from America and the expatriate MAYNARD FERGUSON,

from Canada, met JACK PARNELL on his home ground in an interview conducted

by Tony Brown and Les Tomkins in 1970

Three

famous instrumentalists, now bandleaders—who normally wouldn’t meet—gathered

together in a room at London’s Dorchester Hotel and talked on a wide range

of subjects. BUDDY RICH from America and the expatriate MAYNARD FERGUSON,

from Canada, met JACK PARNELL on his home ground in an interview conducted

by Tony Brown and Les Tomkins in 1970

PARNELL: All right, if you didn’t play for six months, I bet you’d love playing when you got back.

RICH: Well. I haven’t played for sixteen hours, and I’m ready to go back to work tonight. But if I were off for six months, I think because I love to play as much as I do, I wouldn’t have any problems with lack of co—ordination or stiffness.

PARNELL: If you were off for ten, twelve or fifteen years. . . .? What about the time you broke your arm?

RICH: I never missed a night’s work, in spite of the broken arm.

FERGUSON: Yeah—I know that one!

PARNELL: We all know that one.

RICH: It’s really nothing extraordinary. It was a matter of either playing or going hungry—and I chose to eat! Last night I went through all kinds of terrible pain with these teeth of mine; I had a choice of saying: “I can’t continue”, and just playing the first half of the show and coming home here or finishing the job. And I firmly believe that if you have a job to do, you either do it, as good as you possibly can under the most trying conditions, or you simply don’t do it at all. That’s the way it is—show–biz, if you will.

That’s the reason I believe that if you had to do it today, you could pick up a pair of sticks and play, because you are that professional and you are that good. I heard a story about Maynard, with half a tooth; he blew his tooth into the audience, but he managed to play.

Which is the mark, in my mind, of a very professional and very great artist.

I only have respect for that. I have no respect for people who come up, in any given field, do half a job, and want you to know why it’s only half a job—“because I have bellyache” or whatever. If you have that bad a bellyache, the people that are paying their money are not concerned, because they have their bellyaches, too, and they’re there to hear you and forget their problems.

PARNELL: Well, you’ve answered my question for me.

RICH: I don’t remember you asking.

PARNELL: It’s what I said: because I can’t do the job to the professional standard that I want to do it, due to being so out of practice and it being so long since I played all the time—that’s the reason why I don’t play at all.

RICH: Yes, but I think you can do it, because you are that good.

Is it also an obsessional thing to reach a very high musical standard?

RICH: Not an obsession—an ego. If you don’t have any ego, you shouldn’t play to begin with.

But through that ego, doesn’t it become obsessional? You can do it, but the ordinary person couldn’t produce that kind of concentration.

PARNELL: But they produce that kind of concentration in other fields.

Then they’re the creative people in their fields. It’s more than a job of work.

RICH: It’s a job of love, I think. I could never sit in that module upstairs and try and connect the two ships, with all the study and practice in the world, because that’s not my bag at all. But I’d like to see him come down here and play “West Side Story” some night.

They’ve been chosen for that job because they’re the best in their field.

RICH: Yes, but they weren’t the best before they were chosen. They had a potential of being the best. They’ve been making practice trips for ten years.

But great musicians don’t wait ten years and play practice jobs. They start playing professionally right away and theyget better at it all the time. We don’t wait for one specific job; we try to do the same thing day after day of our lifetime. We’re doing our best all the time—for ourselves as much as for the audience.

Maynard, people have often accused you of being an exhibitionist. You are a man of some creativity. How can you relate that creativity to doing a job of also entertaining?

FERGUSON: Both those are a joy to me, and I happen to be the type of person that naturally expresses that joy. I grew up as a vaudeville act, which might be why sometimes I can be an extrovert.

I can also assure you that when I’m unhappy with my band I can be a different kind of an extrovert backstage. But what I do is honest, because I really enjoy what I do in life, and I do it open.

It’s very much like the Indian philosophy of being able to expose your joy, and not being ashamed of words like love and all those new thinkings.

You just go ahead and accept your pleasure, and not worry about whether we wish to call these things exhibitionism, extrovertism, vaudeville within jazz, or any of those old Leonard Feather clichés. Instead of that, if I watch Buddy Rich do a fantastic drum solo with one hand, I sit back and say things like “Bloody hell” and all those English expressions, and I laugh at it with great joy, because I know that he’s enjoying it, even if the other arm hurts a little bit.

And it’s a new challenge to him. He wouldn’t go out and break his arm just to show he could do it, but while it’s there he still has a gig to do, and he does it. And he does it as Buddy Rich.

If I wished to develop a Miles Davis or Chet Baker personality, in order to look for a different form of a write–up in a magazine, I’m truly living a lie and the joy will go.

PARNELL: But that’s their own form of exhibitionism. anyway. isn’t it—what Chet does and what Miles does.

A funny thing has just struck me—you mention vaudeville; Buddy comes from vaudeville and so do I. Strange. It’s been in my family for a hundred years. We’re just a bunch of vaudeville acts—let’s face it!

RICH: But isn’t it all entertainment? Unless it’s so completely commercial that it’s ridiculous. As long as it isn’t against what you’re doing musically. For instance, if you walked out there and you wore a funny hat, in order to draw the attention to what you’re playing, it means that your playing is really secondary to the impression you want to give as far as your appearance is concerned. But if you walk out there and you play, and there’s great technical ability involved in it. so what? We’re all showing, really, ‘what we can do, not only musically but technically and also for the joy and entertainment of our public.

It’s all one thing—entertainment. How honest it is, that’s all.

FERGUSON: And Buddy, part of the band thing that crops up in there, too, is: how to turn your band on.

RICH: They already know!

FERGUSON: In other words, the point is, after you do have your complaints about being driven 120 miles to a lousy studio. because you’re down and you’re attacking the BBC or whoever you’re into, you’ve got to watch out that that band doesn’t go with you. They, in their perhaps less experienced way, will start to show it in the music, and you will then have to turn round and turn your band on—that’s what I mean.

RICH: Yes, there’s no doubt about the fact that your personality affects the people that work for you. If you come in and you’re bugged, and you have sixteen people working for you, and they say something to you . . . If I’m in one of—my most arrogant moods and I have no time for them. musically it’s going to come out just exactly that way.

If I come in feeling great, and they’re brought down, perhaps, because the trip is long, I’m twice the age of most of them, and they would feel a little ridiculous if they started complaining about how tired they were to me. Consequently, they have to react off my reaction. If I feel good, they automatically feel good. If I feel bad, they have every reason to feel bad. And I allow that; I think that’s only fair. Why should I be the only guy allowed to say: “I hate it here at this particular job, but you better love it.” Should I be in a bad mood, I try before the job to get myself together, so that at least I know the band is going to sound half–way decent.

It was mentioned a while ago that all the really great bands have been directed by musicians. Can you think of any exceptions?

FERGUSON: No, not that really lasted. There’s a way of leading, and you can either lead a group in Vietnam—forget that; I’m sorry I mentioned it—or else we can just be a leader in the music thing, which is all to do with us being mystics or we wouldn’t be basically musicians. Music is a spiritual thing, and that’s where our whole game lies.

A spiritual leader is certainly far removed from any other kind. I know sometimes my band plays so good that I prefer not to play, and just to listen to it; those are some of my favourite nights.

PARNELL: Well, you take Bert Ambrose. You would never have called him a good fiddle player, but somehow he had a way of making a band play. He just had leadership.

RICH: Then. of course, you have the exact opposite. You have people like Lawrence Welk; he hires 22 musicians who come in and do their thing. We have people like Guy Lombardo; if he didn’t show up with the baton, the band would sound equally as bad. It would never sound any better. He is what I suppose years ago was called a personality, who dances around and says to the folks: “Good evening” and “What would you like to hear next?” Then you have people who don’t really have anything to say to the audience, because their main concern is to have the band play as good as possible. And they are musicians themselves, who put great demands on their people. That’s why you have Count Basie still around today, doing his thing better than anybody else.

And Duke Ellington, at 70, is still running around like he was 15 years old; the man doesn’t realise he’s 70, and you gotta love him. You have to love people like that, who have only one thing in mind, and that’s their particular art.

And all the other people who do their thing I have very little respect for, because they’re making money and not really giving anything. Again, I don’t suppose the money really means that much. There’s guys like Miles Davis, who has great disdain for his audience, but his talent is there. You have Dizzy Gillespie, who’s a great showman, and you can’t very well put him down because he decides to be a clown up there; that’s Dizzy’s personality.

We had Lester Young, who was one of the great geniuses of all time, and who was completely oblivious to an au’dience or to anything else in life other than his pork—pie hat, his jug and his tenor saxophone. And Charlie Parker —people like that. We can talk about people like that for hours, but we can only talk a few minutes about the other idiots who stand in front of a band, go “1, 2, 3, 4” and don’t do nothing.

It’s possible, isn’t it, for a set of musicians to hate you at a given moment, but they needn’t despise you.

PARNELL: Oh no—hate is a very good thing.

They may say things about you, but underneath it is a lot of respect. Bert Ambrose was respected by the men in his band, because they were afraid of him.

PARNELL: Well. I don’t think it was so much that they were afraid of him. They knew that he knew whether the band sounded good or not.

RICH: A musician is a funny kind of personality; he’ll try to get away with anything.

PARNELL: Not half!

RICH: They’ll try to tell you that they can’t make it tonight—the long trip. or tired or a headache, maybe. And if you’re weak enough to accept that, that’s your problem. You can feel sorry, but we all have this job, “If you really feel that sick, we’ll work with only two trumpets tonight. But don’t do me any favours and go up there and louse up the other two trumpets.”

But musicians do get self–doubts, don’t they, out of their natures. They go through periods when they lose confidence.

RICH: Well, why shouldn’t they? Don’t you? Everybody’s entitled to feel bad.

If you have to wind ‘em up and say: “Okay, fellows, it’s time to play,” it becomes mechanical. Like the Glenn Miller Band, which was laughable to me.

Not only did that band play mechanical, the solos were the same every night; there: was really no improvisation. If it sounded like it fit the arrangement, he insisted that that was the way it had to be played night after night after night.

Well, where does the individuality and the creativity come in? That’s all wrong; that’s just as commercial to me as a thing like Lombardo.

I’m not the first bandleader that’s ever said this, but I think if you have to make a mistake while you’re playing, make it loud so everybody knows it’s a mistake. Don’t sneak it in, because then its obvious. Make sure it’s heard, because that’s an honest mistake, and it’s beautiful. There’s nothing wrong with that. It’s like walking down the street and tripping. You can’t help it. But if it’s caused because of sloppiness and not caring, that’s something else again.

FERGUSON: Have you ever noticed, if you have a great lead trumpet player, and I’m sure you have—if he makes a tremendous wrong entrance your natural reaction is to laugh. Right?”

RICH: Every time.

FERGUSON: It tears me up more than anything else when my lead trumpet player blows it, because I know that he’s, like, got that leader complex, if he’s a good man. And the idea of the old classical conductor thing, of giving him the negative look, so that the audience knows that you’re in total command, that’s another form of phoneyness just as bad as the guy who goes “1, 2, 3, 4” and the other guy kicks it off for real, et cetera.

RICH: Right. I feel that those things have to be allowed. If he makes an honest mistake like that, like coming in wrong, it’s because the intensity is there and the anxiety to do it right. And you might be just that bit too anxious to do it that it’s maybe a beat too soon, or a bar, whatever. But it’s right, because he was ready for it. I don’t resent that, but I do resent the guy who comes in a bar late, because that means that he wasn’t listening at all; he wasn’t paying attention, then somebody said: “Hey, it’s time”—“Oh—“—and it’s late. That’s when I get mad. I have no tolerance for sloppiness.

PARNELL: It’s hard at the time to figure out which way it was,. though, don’t you find? Because there must be something wrong with me, because I hate mistakes. I can’t stand it.

RICH: We all hate mistakes. And I think the man that makes it hates it more than the listener.

FERGUSON: But as long as we’ve got what you were just saying, I don’t hate mistakes.

RICH: Well, if it’s an honest mistake, we can’t really hate it.

PARNELL: There must be something dishonest about me. I can never figure out what’s an honest mistake and what isn’t.

RICH: I make more mistakes than anybody in the history of the music business.

FERGUSON: One thing, though—to be a great drummer, you’ve gotta always feel sure that you’re right. If I can mention one old story; it has to do with Shelly Manne when he was trying to play tymps and everything. which he did a very good job on, with that 41 piece Kenton orchestra. We were rehearsing a Franklyn Marks thing, with the Schillinger slide–rule games going on, and it was really some beautiful music, incidentally.

But the part that I loved about all this was: there was Shelly trying to do one rhythm over here, another over there, and he was doing it all great.

We were only about the third time through this composition; it was very difficult. Forty of US came in: “Bang!” And Shelly came in: “Boom!” afterwards, and threw a fit and said: “Listen, if you guys just wanna screw around!”

RICH: Beautiful! I believe he was right, too. The other forty guys were wrong.

There’s no doubt about it.

FERGUSON: There you go!

When you say you make mistakes, Buddy, you mean you’re making them trying to do something?

RICH: I always try to do something. I’ll be trying to play something that I feel is a little more difficult than the normal thing that I would play in a certain given four bars, maybe. Because I don’t like to repeat a four–bar fill or a four–bar bridge; so I want to try something, and it doesn’t work out.

But are these mistakes that you hear, and nobody else?

RICH: Oh no, —we all hear it, because when I make a mistake, I make it a good one! And so I insist that they count, because I don’t want everybody to be wrong.