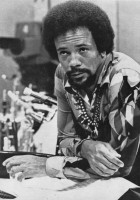

QUINCY JONES

When the going was rough

When the going was rough

A & R work - it's a dictatorship

My band originated with the tour of Free And Easy. We were signed up by a production company which was putting on a Broadway show. They had a contract with Sammy Davis to join the show when we got to England, which was three months after the European tour started. This was the show that Harold Arlen, Johnny Mercer and Arne Bontemps wrote. It was originally called St. Louis Woman, then they revamped it and called it Free and Easy, but it was basically the same story.

The show lasted about three months, then it was in financial trouble and everything, because of the problem of having 70 people and 35 tons of equipment to move around Europe—which isn’t very practical.

And I had very high salaried musicians, because I had probably the best musicians in New York. We had a two–year contract, but it ended up being only three months. So we decided: “Well, we’re in Europe. Let’s stay here and see what we can do.” I think I became 20 years older during this time—it was really rough. But it was interesting. I can’t say it was all rough, because I don’t regret one minute of it. I’ve said many times that I’d never try it again, but that’s a lie, I think. I wouldn’t do that again—but I would try it again.

I would have liked to have experimented more than I did with various tone colours. The band was designed with that in mind—a custom–made vehicle for all the colours in the world. With a guitar player that plays flute and we had, I think, something like 35 woodwind doubles in the reed section alone. Jerome Richardson alone played 11 different instruments.

We wanted to do it—but it was the thing of survival. So we had to stay mostly with the book that we had from records and so forth. We didn’t have time to experiment with it like I really wanted to. But this is the way you grow up, by making mistakes. You take a giant step and jump in the water—and you learn. Now we know that much more planning would be necessary to make a thing like that get off the ground.

The way we’re doing it now is a more practical way, where we go out for three or four weeks and I can get the best musicians available, rather than try to keep a continuous band together. Actually, the band stays together, by virtue of the fact that I use the same musicians for all the recordings I do.

And we play with Tony Bennett, Billy Eckstine, Basin Street East with Peggy Lee—all different type shows. Basically, a band has to have a core to give it a certain spirit. This is the way bands are built. It’s like Basie’s rhythm section. Styles come about by association. It’s a matter of solidifying one conception and spreading it throughout the band.

Now it’s to the point where we have a nucleus of five musicians who were with the original band—Phil Woods, Jerome Richardson, Julius Watkins, Melba Liston and Quentin Jackson. They know this spirit, this philosophy that is the core of the band, and they can spread it, so that at the first rehearsal for any job we can get the band together in two hours. And they would sound as though they’d played together for a year. I’m sure Duke Ellington is in the same position with Hodges and Carney. It’s essential that he has that, sound in the band to keep his sound prevalent.

That’s the reason you want a band to develop the sound. And that’s difficult without working together a lot. So you have to devise every means that you can to get yourself in a situation where the musicians can be around each other a lot. It’s really being around each other, getting mad at each other, hating each other, loving each other and being together—bringing the overall sound to get a common denominator so that everybody wants to go on. This is the way a young band today has to work out, unless you do it like Maynard Ferguson—and he kept his band together. That’s the only way you can do it.

This is where a style comes from. It’s not all on paper. What Duke Ellington writes for his sax section, it takes Carney and Johnny Hodges to make it come alive. Some bands don’t adapt the music enough for dancing. But music is supposed to be danced to. There’s some that should be for listening, too.

Something I liked about the guys in the band was that they all had this same idea. When we were in Sweden we’d play for a one–hour concert—and we had our cake and ate it, too. We’d take a 20 or 30–minute smorgasbord break or something and then go in and play for two hours of dancing. Because there it’s a real participation and communication with the listener.

The ones that want to listen—they listen, anyway. Some dance and listen, some just dance. And we liked that. It was really perfect, because the things that we had that we really wanted people to listen to we would play in the concert segment. In the dancing part they could get a little of both.

As for the question of a big band revival, I think the word revival is wrong. The audience that we’re trying to get to accept big bands now doesn’t know what they are. They’ve never seen a big band. The ones that are supporting the last of the big bands now are the ones that never let ‘em go. That’s Basie and Duke. But the young kids don’t know what trombones are. They’ve never seen three trombones. All they know are guitars, saxophones and coyote quartets. It’s a matter of finding big bands, rather than bringing them back.

So I’m looking forward to my tour here, but I’m not sure what musicians I’ll have in the band, because of this Hatfields and McCoys scene between the American and British unions. About which I think both attitudes are pretty childish. And it’s probably one of them who started it originally—I don’t know.

But the world is so small now and musicians all over the world have one language. It’s a very universal family, very close and tight, and it’s getting closer all the time. All the musicians are playing better—in every country. And I think we ought to just forget all this jazz about: “This one can’t come in”. 802 ought to drop their barriers a little bit about guys coming in for six months. Exterminate all the bad musicians and let the good ones play—wherever they come from! No, I don’t intend to have a full–time band—as of yet. You know, I’m not so much of a masochist this year! But I’ll do it as much as I can. I’ll probably work about five months a year with the big band. Which is good enough.